When General Electric began making cuts to its Schenectady plant, it looked like it was lights out for the once-bustling company town, but these days, there’s a new electricity in the air—and it’s not coming from the old plant on the Mohawk River.

In the last decade, the city has experienced a full-scale renaissance. Thanks to the cooperative efforts of a number of different organizations, Schenectady has transformed itself from a bombed-out industrial shell into an attractive and lively destination for arts and culture.

“Schenectady hit rock bottom about 12 years ago, and since then it’s been pulling itself up by its bootstraps,” says Philip Morris, CEO of Proctor’s Theater in downtown Schenectady.

“Ten years ago, I would [have said that] Schenectady was in a state of shock,” says Joseph Tardi, a member of the 440 Board, a Schenectady organization dedicated to building an arts scene downtown. “After so many years of having GE as a principal, they were now trying to find a direction. Ten years later, even GE is coming back.”

“I don’t think the problem we had was so much different from [that of] other cities. I just think that we worked cooperatively, in a focused manner, and that was the key to making it work,” says Gail Kehn, vice president of visitor services for the Schenectady County Chamber of Commerce. She pauses for a moment before chuckling and adding, “Not that it was easy.”

The trouble all started when the city’s major employers began moving out of the area, says Kehn. General Electric, which employed 40,000 workers, gradually cut its workforce to 4,500, and in 1969 another major employer, the American Locomotive Company, closed its doors for good. People began to drift out of the community and, as a result, surviving businesses lost customers. Soon, the once-vibrant electric city was in a full blackout; storefronts were boarded up, streets were in disrepair, and crime rates soared. And it stayed that way—for a long time.

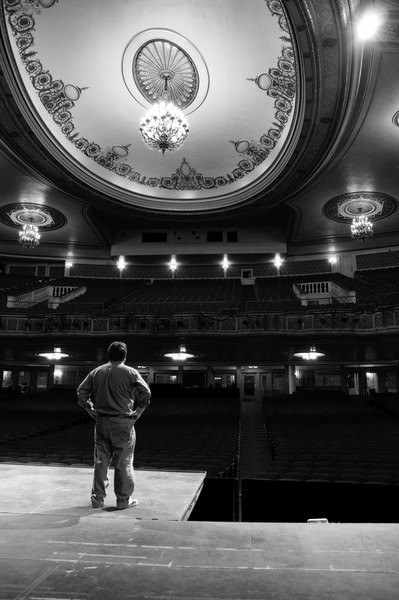

Today, State Street has become a bustling arts and entertainment district, with the Proctor’s and Bow-Tie Cinemas serving as lynchpins for the 10-block downtown area. The two theaters attract huge crowds, and those visitors spend money at other local establishments, including restaurants, artists’ studios, gallery spaces, and performing arts venues.

“Those dollars filter into a lot of different pockets,” says Tardi.

“You’d think that sports is bigger business, but we have seen statistics that show that the arts generates more commerce than sports activities,” says Miki Conn, executive director for the Hamilton Hill Arts Center and a member of the 440 Board since 1999. “These audiences head downtown for a show and end up eating out, or they go to see a movie and end up shopping at the bookstore or bead store nearby.”

Nancy Niefield owns Two Spruce Pottery on Jay Street, and has seen a definite change in the area since she opened her shop in 1988. She points to the lunch crowd from new employers like MVP and the Department of Transportation, but she says that there’s also a weekend crowd from the more distant suburbs. More importantly, these new visitors aren’t just coming for a Broadway show; they’re coming for the day.

“People are coming to make an afternoon out of it, to have lunch, and to shop,” Niefield says. “It’s much more of a destination than it ever was before.”

The theater and the other small venues the theater helped support paved the way for a thriving commercial district. But art-and-commerce is a notoriously tricky pairing—hard to bring together, and even harder to keep together, so how did leaders make it work in Schenectady?

Many people point to an early tribe of arts-minded businessmen who took the reins of Proctor’s Theater in 1988. Headed by then-chairman of the theater Harry Apkarian, this group immediately recognized the important role arts could play in breathing new life into the derelict downtown. “We knew the arts would be a great way to get people downtown,” he says.

When Apkarian came on board, Proctor’s was facing foreclosure: “It was flat on its back financially,” he says. The seasoned entrepreneur, who is now chairman and CEO of TransTech Systems, Inc., set about rebuilding the theater and, in so doing, rebuilt the neighborhood. “Proctor’s gave people hope. When Proctor’s came back, people saw a light at the end of the tunnel. They saw people coming back.”

In 1996, these creative efforts were aligned under the umbrella of the 440 Board, which was incorporated with the mission of creating an arts scene downtown, and in 1998 the city designated the corridor on State Street that extends from Nott Terrace to Erie Boulevard as an arts and entertainment district, thus giving the area an official identity and destiny.

That same year, Apkarian and fellow board members including Union College President Roger Hull lobbied then-Governor George Pataki to create an authority that would be funded through sales taxes. This authority would have the ability to bond projects downtown and make sites move-in ready. The Schenectady Metroplex Development Authority, as it has come to be known, is the commerce portion of Schenectady’s regenerative efforts, a complementary agency whose sole purpose is to recruit and groom the right businesses for downtown Schenectady.

“We had a philosophy. We didn’t want our downtown to look like just any other downtown,” says Scott Cietek, vice president of economic development for the Metroplex. Instead, the agency focused on playing up regional offerings, attracting businesses that are distinct to this area, like Villa Italia, Bomber’s, and Aperitivo Bistro. Once it matches tenants with sites, the Metroplex has the authority to clear most obstacles, whether it is working out parking issues or building a new faÇade. In this way, the Metroplex has secured desirable investors like the Hampton Inn and Bow-Tie Cinemas, as well as local heroes like Angelo Mazzone and Matthew Baumgartner.

Mazzone, who operates a number of successful restaurants in the region including The Glen Sanders Mansion and Angelo’s 677 Prime, was approached by the Metroplex to invest in the neighborhood in 2006. Mazzone bought five buildings on State Street, and remade one into Aperitivo, an urban-chic bistro that caters to the theater crowd looking for a quick bite or drink before the show. The restaurant opened in November 2007 to rave reviews, and its high tables and long bar are filled with a lively crowd most nights of the week.

Mazzone says that working with the Metroplex made the whole project easy. “Ray Gillen [Metroplex chair] coordinated the whole thing,” he says. “And I don’t think anyone could have done what he’s done for downtown Schenectady.”

Matthew Baumgartner owns Bomber’s, a successful bar and restaurant in Albany’s Lark Street neighborhood that is known for its behemoth burritos and wild trivia nights. Last year, Metroplex invited him to open a similar venture downtown. One year later, and he has just closed on his $500,000 location on State Street and can’t wait to open its doors. “It’s been an amazing experience. I don’t know many cities with agencies whose sole responsibility it is to bring business to the area. [The Metroplex] really pulled for it and facilitated the whole thing,” Baumgartner says.

The key to all that facilitation, of course, is money. (“How much money can you throw at it? That’s what it all boils down to,” explains Cietek. “The greatest idea—if you don’t have any money—that’s what it stays: a great idea.”) To fund what it does, the Metroplex collects a portion of the sales tax, about .5 percent, or $8 million last year. This gives the agency a budget for planning, financing, and maintaining buildings within the district.

Over the course of the last 10 years the agency has spent about $60 million removing stumbling blocks for prospective tenants, which in turn has translated into $300 million worth of public and private investment downtown. This represents a level of investment that is usually found only near arenas or manufacturing plants. “We had none of that,” Cietek says with a laugh. “We started around a 2,600-seat vaudeville theater.”

Metroplex got the development ball rolling by persuading MVP Health Care to expand their headquarters downtown, and they lobbied hard to bring the state’s Department of Transportation offices downtown. These large employers provided a foundation for growth, putting workers on the streets at lunchtime and after work. Next, the area needed a movie theater, so Metroplex vetted 15 different companies before settling on Bow-Tie Cinemas, a Connecticut company with proven track record in first-run movies. The six-screen theater opened last year, and welcomed a whopping 300,000 visitors, making it the second-highest-grossing theater in the region.

The Metroplex also worked with the Downtown Schenectady Improvement Corporation to administer funds to fix up the street, first reconfiguring the parking, and then helping businesses repair their faÇades. Last year, the DSIC spent about $400,000 in federal grants, local grants, special assessment fees, and donated monies to keep downtown looking beautiful, says Jim Salengo, executive director of the DSIC.

Meanwhile, the little “2,600-seat vaudeville theater” was in the middle of its own transformation process. In 2002, Morris was named CEO, and over the last six years, he has headed up $40 million worth of improvements to the facilities and programming. In 2006, the theater expanded its backstage area, making it possible to stage large-scale Broadway shows there. “We’re the only theater between Buffalo, Montreal, and New York City that has Broadway shows,” Morris says. The theater also added educational facilities, including an IWERKS movie theater and accompanying curricula in 2007. Last year, 75,000 kids participated in the programs, Morris says proudly.

Proctor’s, the 440 Board, DSIC, and the Metroplex have also worked cooperatively to create additional arts spaces downtown, including studios and exhibition spots on Jay Street. Jay Street Studios opened in 2005 and now serves as a home base for seven artists, and in 2006, four adjacent storefronts were leased to arts-based retail, including the soon-to-open Mohawk Valley Guitar. The groups also host Art Night the third Friday of every month, when shops and restaurants in the district stay open later for exhibitions and performances. This June, the arts and entertainment district was officially renamed ElectriCity, a fitting name for the reenergized neighborhood.

This now-thriving district welcomed between six and seven million visitors last year, which is on par with a midlevel mall. The block around Proctor’s had a five percent occupancy rate in 1998, and today, 95 percent of those buildings have tenants. “Between the Proctor’s schedule, and the movie theater’s first-run shows, you’ve got something going on every night of the week, 365 days a year,” Cietek says.

This type of action is exciting for the local businesses that get a piece of all that discretionary spending, but it is also exciting for bigger companies, who see Schenectady as a location that would attract good employees and clients. “Companies say that their employees want to be in an ‘Ally McBeal’ type of experience,” says Cietek. “They want something eclectic, something lively, something flexible, with ready opportunities for fun.” By building up its arts and culture identity, Schenectady also becomes attractive to big employers.

“This is the trend. If a city is going to make it, it can’t just rely on retail, it has to supply a lifestyle,” says Tardi. “You have to give people a reason to come, something to do.”

The district’s success is also a testament to the transformative power of the arts, and it shows how arts and culture can be a coalescing force for a community, providing a center around which to gather.

“The same as blight spreads, the opposite is also true. You develop a good core, and then that spreads outward,” Kehn says.

“Arts is inspirational. It feeds the spirit in a way that grocery shopping just doesn’t,” Conn says. “It makes you feel like your community is worth saving.”