In January 2011, a 9mm bullet, fired point-blank from the gun of a mentally ill assailant, passed through the left rear of Gabrielle Giffords's head and exited just over her left eye. The Arizona congresswoman, who had been meeting with constituents in front of a supermarket near Tucson, would survive—despite massive trauma to the left side of her brain, the regions that control vision, movement, and speech. After surgery and intensive therapy, some 10 months later Giffords could respond to TV journalist Diane Sawyer's interview questions with mostly one-word answers—yet she could sing all the lyrics of "Tomorrow" from the Broadway show "Annie." Struggling to find language, she would call a chair a "spoon," but she could belt out all the words to Cyndi Lauper's "Girls Just Wanna Have Fun." It was music that helped pave a road back to speech, and it was music that—in the form of a guitar-strumming therapist by her side to help organize her movements—even supported Giffords's steps as she relearned how to walk.

In a brand of health care that dovetails with the beaux arts (think "doctor turned artiste"), creative arts therapies are cropping up everywhere these days, from hospitals and rehab centers to group therapy and workshop settings. Expressive arts such as music, drama, dance, writing, and the visual arts have a wide range of applications and can be tailored to help people with such diverse diagnoses as autism, anorexia, and post-traumatic stress. Music therapy in particular has some solid research behind it: The neurologist Oliver Sacks wrote about his studies on the subject in Musicophilia (Vintage Books, 2008), a book that brims with Sacks's remarkable experiences with patients whose relationship to music deepened after being struck by lightning, or while coping with diseases like Parkinson's and Alzheimer's. Scientists have long suggested that while language is largely held in the left side of the brain, music activates regions in both hemispheres, as well as areas deep within the brain that hold memory and emotion. That's why song lyrics can act like a superhighway (or a bumpy country road, as the case may be), connecting music and speech for people suffering from stroke, dementia, or brain injuries like Giffords's. It is this unique "whole brain" approach that makes music, and perhaps some of the other expressive arts too, so richly promising therapeutically.

Healing the Hurt Psyche with Drama and Song

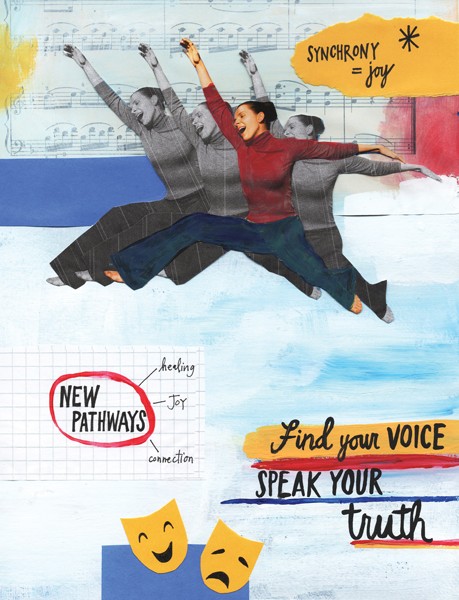

Psychiatrist Bessel van der Kolk—a renowned trauma expert and author of several books, including The Body Keeps Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Treatment of Trauma (Viking, 2014)—contends that drama, song, writing, and other expressive activities are more effective than talk therapy. "We're always looking for new ways of opening in the dark. Traditional therapy doesn't always do that; it clamps people down and makes them behave," says the Dutch-born and Boston-based doctor, who is leading an experiential workshop at the Garrison Institute from April 29 to May 2 for health professionals, artists, and anyone interested in exploring the healing of traumatic stress through acting, songwriting, movement, and other modalities. "This is about people opening up and being free to feel what they feel and know what they know. It's allowing yourself to feel your body, hear your voice, and speak your truth." For people recovering from trauma, this is a radical departure from their usual experience. "The issue with trauma is that you're not allowed to feel what you feel because it's too dangerous," explains van der Kolk. "It's overwhelming—it's too much to know that you've been raped, or you've been beaten by people who are supposed to care for you. To actually find your voice is an act of assertion, and, in a way, of defiance. Doing this through song is an age-old tradition. The civil rights movement was founded on people singing 'We Shall Overcome'; music has always been an important part of people asserting their reality."

Part of what makes group arts like dance, drama, and song so powerful is that they are "synchronized" activities—they help people to be in synch with themselves and others. "The function of our brain is to be in synch with each other. When you get traumatized you get frozen; you get stuck in hyper-arousal. You lose this synchronicity to yourself and to people around you," says van der Kolk. "For veterans, their brains and bodies have changed from being in gear with fighting wars and killing people. When they come home they're out of synch with other people. It's a deep internal feeling of alienation, of being godforsaken, that people don't get me." One of his favorite synchronized activities for trauma survivors is theater: The workshop at the Garrison Institute will include a program called the Feast of Crispian, which teaches post-deployment service vets how to play roles in a Shakespeare play. "It's people moving together, adjusting their bodies to each other in the play situation. They rediscover how to be in synch after dealing with horrendous things."