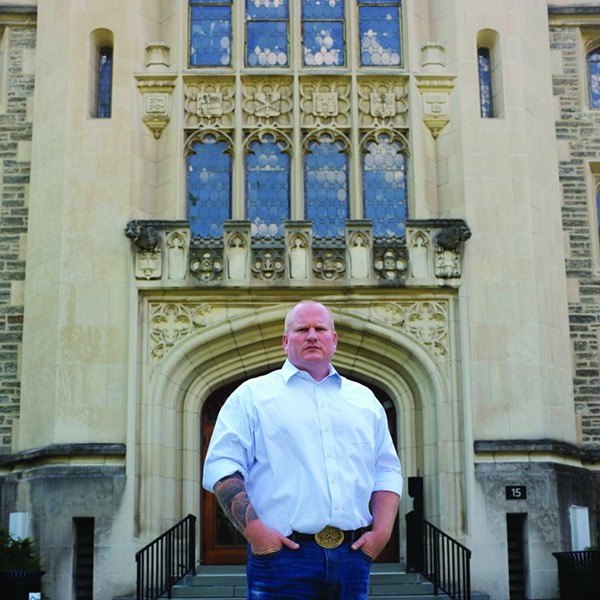

With the escalation of violence now engulfing Iraq, Jimmy Massey, 31, a Staff Sergeant in the 3rd Battalion, 7th Marine Weapons Company, has decided to break his silence and speak out about us abuses on the ground there. A 12-year Marine veteran, recruiter, and trainer, Massey was in charge of a platoon of 30 snipers. “In a month and a half, my platoon and I killed more than 30 civilians. We would take over villages and control checkpoints. My men and I would fire warning shots at oncoming vehicles. But if they didn’t stop, we didn’t have any qualms about loading them up,” he says.

After serving in the first waves of attacks in the war against Iraq, Massey said his farewell to arms on April 18, 2003, and was honorably discharged in November. Today, back home in the Smoky Mountains of North Carolina, Massey wants to bring down the walls of ignorance blinding his compatriots to the realities of the ground war in Iraq, and to rid himself of the remorse that keeps him awake at night. “I’m embarrassed by what we’ve done over there, and I’m on a redeeming and spiritual mission to heal so I can sleep again. When I read about the mutilated, charred bodies of the Blackwater mercenaries in the news, all I thought was that we did the same thing to them. They would see us debase their dead all the time. We would be messing around with charred bodies, kicking them out of the vehicles and sticking cigarettes in their mouths.”

Another soldier, a 23-year-old Marine who returned from Iraq last fall and wishes to remain anonymous, adds, “We would defecate on and run over dead Iraqi bodies.”

Several Marines who have attested to similar experiences remain too frightened of reprisals from the Marine Corps to disclose their names publicly. While Massey hopes that his testimony will inspire others to speak out, he too has had moments of fear. “I have always been aggressive in everything I’ve done and I have been about my stance. I told them when I left, ‘I am going to tell everybody about what I have done.’ I have to tell you, I feared for my life on the drive home from California to North Carolina.”

Checkpoint Homicide

A scene plays out over and over again in Massey’s memory, prodding his conscience at every turn. It is early April 2003, on a road in suburban Baghdad, shortly after the invasion of Iraq. “It was very warm that day, and Baghdad hadn’t fallen completely. A red Kia Spectra sped toward our checkpoint at about 45 miles per hour. We fired a warning volley above it but the car kept coming. Then we aimed at the car and fired with full force. I made eye contact with the driver. The Kia came to a stop right in front of me, three of the four men shot dead, the fourth wounded and covered in blood. When he saw that his brother, the driver, was dead, he collapsed and fell to the curb, waving his arms frantically. And when we were pulling his brother out, he started running and screaming, ‘Why did you kill my brother?! We didn’t do anything!’”

A knot in his throat, Massey pauses before continuing in a low voice: “We searched the car and found no weapon. We called the medics. They arrived 20 minutes later and dumped the bodies on the side of the road. After the shooting, a team of reporters came up. We were told to ‘get them out of here quickly.’ A little later, the same scenario was repeated with two more vehicles. We killed three more civilians. It was a real bad day.” Repeatedly, Massey watched as badly injured Iraqis were “tossed on the side of the road without calling medics.”

He held out for a month and a half in this upside-down universe where, he says, “We were told that Iraqis were loading ambulances up with explosives and that soldiers were dressed as civilians. But when we realized we were hearing no explosions, we started to wonder. Iraqi military compounds had nothing in them, except for dismantled tanks, equipment that was barely functioning, and barracks that looked like ghost towns.” For a while, as several of his platoon members expressed their concern to him about the high number of civilian casualties, Massey repeatedly told them, “Suck it up, we’ve got a job to do.”