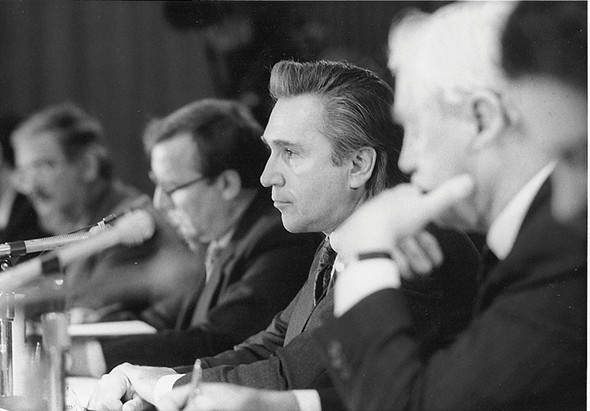

Former New York Congressman Maurice Hinchey is famous for his voice—a passionate, courageous voice that was an agent of change for decades, both locally and nationally. Before Hinchey retired in early 2013 after 38 years in public office, it was his voice that spoke up for environmental conservation, human rights, and economic opportunity, and that spoke out against polluting corporations, organized crime, and the Iraq War before it was politically popular to do so.

Yet Hinchey's family announced this summer that the 78-year-old statesman has been suffering for the past five years from a progressive neurological disorder called frontotemporal degeneration, which is gradually and insidiously eroding the language center of his brain—leaving the once highly verbal man at a loss for words. The announcement arrived at a peak moment during the American healthcare debate, as lawmakers were attempting to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act. In Hinchey's story, the deeply personal becomes the political, underscoring the need for legislation that protects the rights of people like him who find themselves requiring long-term medical care from a team of skilled providers. It is also a story that gives insight into a neurological disorder that most people, even many doctors, have never heard of—and the plight of millions of patients who suffer from rare diseases, often misdiagnosed and relegated to the outskirts of our much-needed awareness and understanding.

When Words Slip Away

Maurice Hinchey—a onetime navy sailor, toll collector, cement plant worker, and literature scholar—has been no stranger to medical uncertainty. Just after announcing that he was running for Congress in 1992, following 18 years in the New York State Assembly, Hinchey suffered from what doctors call profound sudden hearing loss. His hearing went out abruptly, for no discernable reason, and came back intermittently. After a course of steroids, his auditory function returned completely—but only in his right ear. "He went through Congress with one ear working," says Hinchey's wife, Ilene Marder Hinchey. Then, during his last congressional term nearly 20 years later, Hinchey underwent successful treatment for colon cancer. It was a few months later, at the end of his term, that the family noticed a change in his language pattern. "Like many of us, he would lose a word every once in a while, but it began happening more frequently," says Marder Hinchey.

Certain words weren't just hard for Hinchey to find—they seemed to have vanished completely, as if erased from his consciousness. He went for testing, and a brain scan returned a diagnosis of frontotemporal degeneration (FTD), a progressive, fatal disease that gradually damages the brain's frontal and temporal lobes. After facing sudden hearing loss and a curable form of cancer, Hinchey was coming up against something unbeatable. Currently, FTD has no cure, nor does it have any treatments to slow or stop its progression.

"FTD is a form of dementia," explains Susan L-J Dickinson, CEO of the Association for Frontotemporal Degeneration (theaftd.org), based in Pennsylvania. "But it differs from Alzheimer's disease, the most common form of dementia, in three critical ways." Unlike Alzheimer's, FTD does not attack the memory center of the brain—instead, it can affect a person's behavior, language, and movement, leaving their memory and ability to recognize people relatively intact. It is also rare, with about 55,000 diagnosed cases compared to the 5.5 million people in the US with Alzheimer's. "A third way that FTD is different is that it hits people, on average, about 10 years younger than Alzheimer's," says Dickinson. "It can impact people anywhere from their 30s to their 80s. FTD is actually the most common form of dementia in people under age 60."

No two cases of FTD are exactly alike, as different variants of the disorder can produce very different symptoms. For Hinchey, the disorder started with a slow decline of his language function, manifesting in what doctors call primary progressive aphasia. As the disease has advanced, Hinchey has also developed a variant of FTD called Parkinsonian syndrome, marked by a decline in movement. "It's not Parkinson's disease," says Marder Hinchey, "but some of the symptoms are similar. They're not extreme. He might have a slight tremor in his leg from time to time, and he has some stiff muscles, affecting his ability to move." FTD is a slow disease with plateaus that people get to live with for a period of time. But the symptoms will eventually progress. "For much of the time [he's had FTD], Maurice was going out to dinner, having conversations, going to movies. It was only in the last year that he even began walking with a cane." But the plateaus can change very quickly, bringing health issues that require skilled, round-the-clock nursing care.