When people think of extinction they think of whales, California condors, tigers. I'm very much focused on the slow, invisible losses of crop diversity—not just having the library burn down, but losing an individual book now and then," says Cary Fowler, a scientist, conservationist, and biodiversity advocate, who is best known as the mastermind behind the Svalbard Seed Vault.

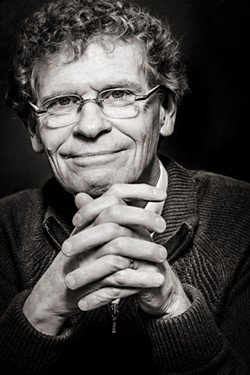

Though approaching 70, Fowler's kind face is framed by boyish, strawberry blonde curls. He has a strong chin and expressive blue eyes set behind gold wireframe glasses. A lilting drawl hints at his Southern upbringing.

Fowler was raised in Memphis and spent summers at his grandmother's family farm in Madison County, Tennessee. These visits cemented an appreciation of farming, which has been at the heart of Fowler's career.

Public Service

Fowler comes from a long line of public servants. His father was a judge and his paternal grandfather was the head of the Memphis Housing Authority. On his mother's side, his grandfather was Commissioner of Education for Jackson, Tennessee, until his death. "Agriculture in my family was seen as public service," he says. "I suppose I was poised to try and marry those influences."

Amidst the political turmoil of the civil rights movement, Fowler strove to find meaningful work. In his early 20s, he worked for the Institute for Southern Studies in North Carolina, which published a journal called Southern Exposure. He wrote a piece for the publication about the rapid disappearance of family farms like his grandmother's. "That was the first thing I had ever done concretely about agriculture." The article was a jumping off point for Fowler, who subsequently began researching farming and the various challenges the industry was facing as it shifted away from small farms and toward large-scale monocultures. This trail eventually led him to the underpublicized issue of diminishing crop diversity.

Fowler read the work of Jack Harlan, an American scientist and plant breeder whose startling articles bore provocative titles like "The Genetics of Disaster." He learned that due to social and environmental factors like urbanization, the industrialization of farming, and the standardization of seed supply, large numbers of local crop varieties and their wild relatives were disappearing at a rapid rate. "I thought to myself, 'If the most knowledgeable scientist in the world is ringing the alarm bells this loudly, then it must be an important issue.' But the politicians and the powers that be weren't paying a lot of attention." So Fowler became an interpreter for the masses, working to popularize Harlan's scientific work on crop diversity and to get people to pay attention.

Willpower or Dumb Luck?

At 23, with this new career just budding, Fowler was diagnosed with terminal melanoma. The doctors gave him six months to live. Against the odds, he recovered. However, a decade later, in 1982, he was diagnosed with seminoma, a completely different cancer, though again terminal. He says, "The second time I just didn't believe I would die."

Whether through sheer willpower, divine intervention, or dumb luck, Fowler did survive again. With good-humored defensiveness, he says, "Most people make more to-do out of the cancer stuff. I was pretty determined and focused before I got cancer. It wasn't like a conversion experience. But I don't have a control group, so I don't know what my life have been like without that."

Throughout the 1980s, Fowler worked long hours writing, lobbying, teaching, and researching. By the early '90s, he was internationally recognized as an expert in the field of plant genetic resource conservation. The United Nations commissioned him to lead a global assessment of the state of crop diversity and strategize a plan for conservation and use of these resources. Fowler's team found that the UN's much touted "global system" of gene banks was not preserving much of anything. Instead, the underfunded facilities were sites of ongoing deterioration—faulty cooling systems, high humidity, and other technical problems involved in archiving were resulting in the destruction of seed samples. The study made exceedingly clear how much work remained to be done to ensure the future of crop diversity and food security.

In 2003, Fowler was splitting his time between the Norwegian University of Life Sciences and the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). CGIAR's seed samples were not all housed in secure locations nor did they have safety duplicates. An abandoned mine shaft in the mountains of the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard was one of the few repositories for duplicate samples in the world, which gave Fowler and his colleagues the idea for the Seed Vault.