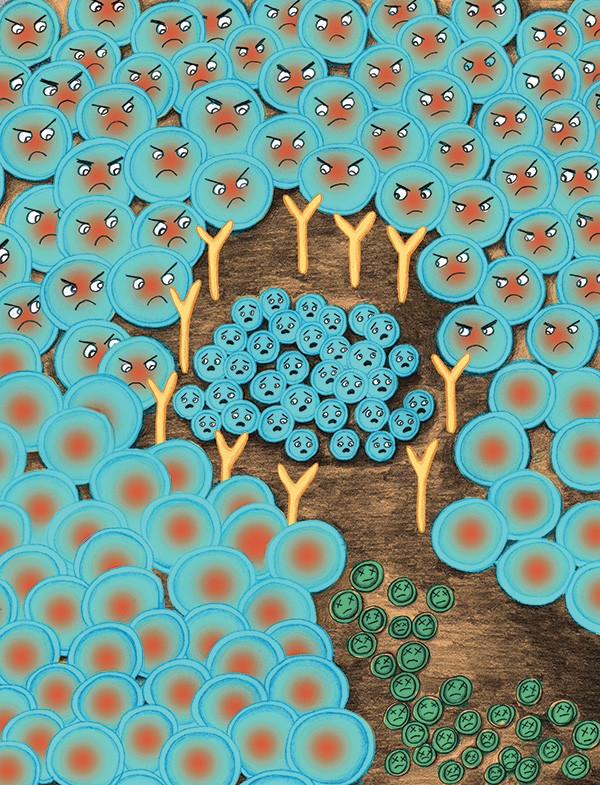

For an estimated 50 million Americans, there's a war going on inside the body. As far as wars go, this one is senseless—even downright insane. Picture this: Suddenly, without warning, the Navy SEAL defense corps that is the human immune system goes on a metabolic rampage. White blood cells, like millions of tiny soldiers gone haywire, begin to infiltrate a chosen area—whether it's the pancreas or liver, gastrointestinal tract or brain. Yet instead of going after a foreign intruder such as harmful bacteria, they are assaulting healthy, innocent body tissue. It's as if these cells have collective amnesia and have forgotten the difference between "self" and "nonself." The result is an insidious inflammatory response, a sickness where none existed before and where none ought to exist—and a disease that is often as hard to treat as it is to understand.

This is not the Twilight Zone. It's autoimmune disease, and it's very real—even more ubiquitous in our culture than cancer. Yet despite its prevalence, many people don't really know what an autoimmune disease is; though researchers have identified some 80 to 100 of these disorders, 85 percent of Americans can't name even one of them. Individually, many of these illnesses are well known—such as multiple sclerosis (in which the body attacks the central nervous system); type 1 diabetes (target: the pancreas); and ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease, and celiac (the GI tract). Others are lesser known, like vitiligo, a form of autoimmunity resulting in loss of skin pigmentation (Michael Jackson had it). A few, like lupus and rheumatoid arthritis, are systemic—meaning the self-attack crosses organ lines and affects many areas throughout the body. In addition to their autoimmune nature, there's one more thing that these widely disparate illnesses all have in common: They're on the rise.

When the Body Turns on Itself

"We're seeing more autoimmunity, there's no question about it," says Kenneth Bock, MD, who practices integrative medicine in Red Hook. Among the disorders he's encountering more frequently these days is Hashimoto thyroiditis, a self-attack of the thyroid gland ("It's so common now, it's incredible"). And science confirms that over the last three decades, autoimmune disease in first-world countries has been soaring to nearly epidemic rates. A 2008 study in Finland showed that incidence of type 1 diabetes (not to be confused with type 2 diabetes, which is not autoimmune in nature) had more than doubled in the previous 25 years, while a study of blood registries in Minnesota found that celiac disease is four times more common now than it was in the 1950s.

Why is this happening? There are as many theories as there are autoimmune disorders. Some cite the "too clean" hypothesis—with the eradication of so many bacteria and pathogens from widespread antibiotic and antibacterial use, the immune system has too little to do and thus turns on itself, as if out of boredom. Others take the opposite tack and blame environmental toxins for an immune system gone loco. Since about three-quarters of autoimmune patients are female, some researchers see hormones as a factor. In fact, all of these theories, and more, are probably true: Autoimmunity is not only multifactorial but also cumulative. "I call it the immune kettle," says Bock. "When you get all these factors, then the kettle will overflow and boil over. That's when immune imbalances and clinical symptoms appear, and ultimately you get these disorders and diseases. In the kettle are many things, some of them toxins. Heavy metals are known to promote autoimmunity—mercury, lead, arsenic. BPAs, and plastics can push autoimmunity." Recently banned by the FDA, trans fats—which entered our diets after World War II, just before autoimmune disease began to skyrocket—have been linked to autoimmune potentiation. Vitamin D deficiency is another known link. A recent study even found salt (or the iodine in it) to be a possible culprit. Then, of course, there are genetic factors, which are complex. What many people don't realize is that autoimmunity can run in families, popping up in unexpected and seemingly unrelated ways.

It's All in the Family

For Eve Kunkel, a patient of Bock living in Salt Point, autoimmune disease is a family affair. Her mother has vitiligo and her sister has autoimmune hepatitis. But it wasn't until she had her own children that Kunkel realized just how autoimmunity can spread itself across a family tree. Although she is disease free ("I dodged that bullet," she says), all three of her sons—ages three, seven, and eight—have autoimmune disorders. "Dr. Bock had always said, be aware that autoimmunity is in your family and it can pop up out of nowhere," says Kunkel. And it did. Her oldest son one day developed a nose twitch—"a constant twitch, like a bunny"—and the pediatrician shrugged it off as nothing. It was Dr. Bock who recognized it as a sign of PANDAS, a pediatric autoimmune neurological disorder that can arise with strep throat infection. He treated it with antibiotics, and the twitch went away. Last year, Kunkel's youngest son, at two years old, was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes. He also has celiac disease. "No one in my family has type 1 diabetes," says Kunkel. "But we have autoimmune disease, and that's where the connection comes. Physicians don't always see that connection. They ask, 'Do you have type 1 in your family?' If the answer is no, then it's dismissed."

Kunkel's family is lucky—many autoimmune patients suffer for years before doctors correctly diagnose them. According to the American Autoimmune Related Diseases Association (AARDA), it takes an average of five years—and five doctors—to arrive at an autoimmune diagnosis. Patients are often shuttled from specialist to specialist looking for answers. But modern medicine's tendency to compartmentalize diseases into distinct categories is not well suited to addressing autoimmunity, which in many cases resists compartmentalization. And since autoimmunity as part of a patient's family history is not a standard question on doctors' health surveys—though it ought to be—physicians often miss the boat when it comes to this diagnosis. "The experience I've had with many doctors is 'let's wait and see,'" says Kunkel. When she was suspecting type 1 diabetes with her youngest son, a pediatrician suggested waiting a week, saying that if it was indeed type 1, he would get really sick. "Do I need to wait until he's really sick?" she asked.

It's no wonder that Kunkel has found an ally in an integrative physician like Bock, who, unlike a specialist, uses a whole-body, whole-person approach to see the bigger picture. Last year, when her middle son started urinating more frequently, Kunkel suspected type 1 diabetes for him as well. "I immediately brought him to Dr. Bock. I was a mess sitting in the chair, terrified. But when I ran through the symptoms, he asked, 'Is there anything else?' I said, 'Well, he's been blinking a lot.' Dr. Bock said, 'It's not diabetes—it's PANDAS.' And it was. I was amazed. You hand him the pieces and he puts them together."

Changing the Medical Mindset

It might take something like an autoimmune epidemic to hold up a mirror to our health care system and reveal its shortcomings. Modern medicine's insistence on treating the symptoms of disease, rather than the causes—a pattern dictated in large part by the pharmaceutical companies—will do little to address these complex and chronic disorders. Slowly, though, we're starting to see signs of change, including a new way of viewing autoimmunity as one entity. "It's been a paradigm shift to get the public and even health professionals and the government to think of autoimmunity as a disease category that has a common disease pathway and a common genetic background. They were thought of very separately in the past," says Virginia Ladd, the president and executive director of AARDA. Like similar organizations, AARDA focuses on supporting research into autoimmunity. But fundraising is a challenge. "The amount of money put into autoimmune research is pretty small compared to the incidence and the cost of these diseases," says Ladd. "Philanthropists and donors are very loyal to their particular disease, whether it's MS or diabetes." What the people writing these checks ought to consider is that we might need to support research in autoimmunity as a whole in order to make progress in the fight against any one of these diseases individually.

On its limited budget, AARDA also focuses on increasing awareness—"particularly that these diseases run in families," says Ladd. "There's always difficulty in getting a diagnosis, and that's one of the clues—if someone in the family has another autoimmune disease. It doesn't have to be the same one. Research has supported that in fact this is true, which led to more genetic studies that showed the disparate diseases shared many common genes." Yet rather than finding one gene as a marker for autoimmunity, research has found several. "It's more a plethora of genes together that initiate an autoimmune response," says Ladd. In other words, the plot thickens.

Inner War, Inner Peace

Thankfully, genes are not the whole story: Certain diet and lifestyle changes can help to ease the impact of autoimmune disease. "You can't control your genes, but you need to be aware of them," says Bock. "Then you can be more preventive in your family about things that may contribute to the autoimmunity." Depending on the disorder, one treatment approach might involve identifying and eliminating a toxin—whether it be a dietary allergen contributing to inflammation such as wheat or dairy, heavy metals from fish, or even a virus or bacterial infection such as strep throat. Then there are proactive measures, such as adhering to a regimen of supplements that are known to help regulate the immune system. "I call it the holy trinity: probiotics, omega 3s, and vitamin D," says Dr. Bock. "This combination enhances a beneficial group of lymphocytes in the blood called T-regs, which can reduce inflammation." In Kunkel's house, supplements like these, along with mindfulness in the kitchen, have had a visible impact on the family's health. "We've been strictly organic, and we stay away from processed foods," she says. "I do a lot of cooking—fresh meals, nothing from a box." Despite their autoimmune diagnoses, Kunkel is pleased to find that her children are otherwise extremely healthy.

Yet more research, and a much more integrative approach to health care, are essential to ending the wartime state that prevails in so many of our bodies. "We have cancer centers all over the country, but not one autoimmune center," says Ladd. With the establishment of a such centers for research, treatment, and diagnostic triage, we could pick up the speed toward making biological peace—and eradicating the insane war that is autoimmune disease.

RESOURCES

Kenneth Bock, MD (845)758-0001; Bockintegrative.com

American Autoimmune Related Diseases Association Aarda.org