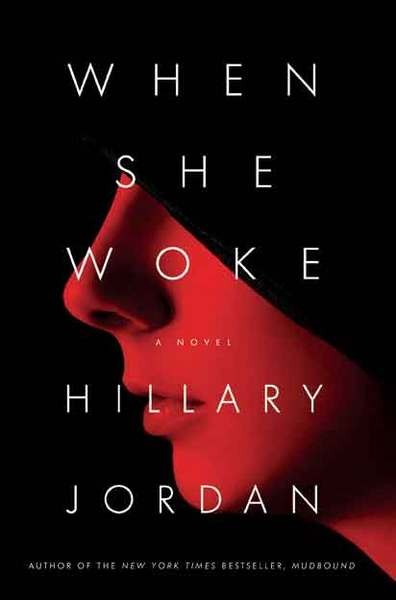

When she woke, she was red. Not flushed, not sunburned, but the solid, declarative red of a stop sign.

Jordan breezes into an Italian café near Grand Central Station, wearing a peach-toned sleeveless blouse, black jeans, and sandals, a large bag slung over one shoulder. She could as easily be a late-summer tourist as an award-winning novelist on the brink of a major book launch—at least until she pulls out a scarlet iPad to display her tour schedule. Between now and mid-December, she’ll appear at three major trade shows and 34 author events nationwide; When She Woke is Indie Next’s #1 pick for October.

The whirlwind is just getting started, but Jordan has been there before. Her debut novel Mudbound (Algonquin, 2008) won the Bellwether Prize—a biannual award for socially responsible fiction founded by Barbara Kingsolver—and numerous other honors. A saga of complex family ties and brutal racism, it unfolds in rural Mississippi post-WWII, as two traumatized soldiers return to a hardscrabble cotton farm. Jamie is the glamorous, broken brother of new owner Henry, Ronsel the proud son of black sharecroppers; their fates intersect with tragic force. Mudbound received glowing reviews and sold more than 250,000 copies worldwide.

Such a breakout success is a hard act to follow. “Writing when you don’t know if anybody but your parents will ever read it is very different from writing under contract,” Jordan asserts, after asking a waiter for “iced tea—no sugar, no lemon, nothing.” As Mudbound’s sales climbed, Algonquin offered her a two-book contract, accepting the opening chapters of When She Woke as the first. This was an act of no small faith, since the two novels are wildly different.

Where Mudbound is a period piece, When She Woke takes place in a dystopian future a generation or so away, and too close for comfort. The US government has become a fundamentalist theocracy that resembles a Rick Perry rally on steroids (now known as “nanoenhancers”). It’s as if Jordan has watered the Monsanto seeds of today’s Christian right and let it grow like Jack’s beanstalk. Her Texan landscape is just outside the familiar—strip-mall chains mix new and old corporate logos; local readers may note there’s a coffeehouse called Muddy Cup.

In this new society, prison overcrowding has been solved by “melachroming” criminals: chemically tinting their skins and releasing them onto the streets, where they’ve become a despised new underclass—literal people of color. When Hannah Payne wakes up as a Red, everybody who sees her knows she’s been found guilty of murder: Her full-body Scarlet A stands for Abortion as well as Adultery.

Jordan is not the first writer to riff on Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter—Suzan-Lori Parks’s plays In the Blood and Fucking A remix the tale of Hester Prynne, as does the recent teen flick Easy A. But she may be the first to vault it into the rarified realm of literary dystopia colonized by Margaret Atwood and Doris Lessing.

Like Hester Prynne, Hannah refuses to name her lover, a powerful man of the church. For some readers, Jordan’s most audacious creation may be Aidan Dale, a charismatic megachurch preacher of true faith and conscience. Though it’s certainly less cliched than portraying him as an opportunistic hypocrite, one might well wonder if such a person exists. “Billy Graham. By all accounts, he was a true man of God,” Jordan says, adding, “I didn’t want When She Woke to be a condemnation of faith. But I’m not a big fan of fundamentalism. In every fundamentalist religion, women are disempowered.”

Jordan grew up in the Episcopalian church. Though her parents were “not really believers,” her grandparents on both sides were devout. “I’m probably a secular humanist, but I’m still trying to figure it out,” she says. “While working on this book, I found myself really thinking a lot about faith and spirituality.”

The book’s bold premise also stems from within Jordan’s family. Many years ago, her uncle opined over dinner that all drugs should be legal, but they should turn you bright blue. “The conversation stuck in my mind and eventually bore this dark, strange, red fruit,” Jordan writes in her acknowledgments. She chose the color red for its associations with blood, rage, shame, red alert, Red States; Red was the book’s working title. The Scarlet Letter connection came later, as did the abortion storyline—in early drafts, Hannah was Chromed for killing her sister’s abusive husband.

“Abortion is one of those things about which intelligent people can disagree. I believe it should be legal and rare,” Jordan says. “I can sympathize with why people might disapprove of it personally, but I don’t think that’s something anyone should impose on anyone else.”

Those are fighting words in much of this country, and while she expresses concern about whether Mudbound’s many fans will embrace When She Woke, Jordan has no regrets. “I really wanted to get out of the past, to get out of the Jim Crow South, to get out of first person. I hope I will always be the sort of writer who does something different with every book,” she asserts with characteristic intensity. “After 9/11, I became very concerned about things that were happening in this country—government incursions into privacy, the rise of the religious right, laws limiting women’s choices, environmental degradation, the muddying of the line between church and state.” These concerns fed and shaped When She Woke.

It was a difficult birth. “I wanted the reader to be very close to Hannah, moment by moment, but her head was not always a fun place to be. This world was not always a fun place to be. I definitely went though some dark periods writing this book,” Jordan admits. “I literally wrote it not knowing what was going to happen in the next sentence, the next scene, the next chapter. It was dizzying at times, having every possibility be open. There were many moments of ‘What am I doing?’ But this is my process. Writing the book was probably a lot like it is for you to read it: What will happen next?”

Short answer: plenty. Hannah goes from a televised solitary confinement cell to a halfway house called the Straight Path Center, whose name and ritual manipulations suggest “pray away the gay” conversion therapy. There she meets Kayla, a feisty biracial woman who was Chromed for shooting her abusive stepfather. They go on the lam in “a converted Honda Duo so old it had no smartfeatures, not even a nav.”

Two female Reds traveling together are a magnet for violent males, but others are monitoring their movements as well. An underground group offers to smuggle them to sanctuary in Canada, a treacherous journey that echoes the Underground Railroad and networks of safe-houses for battered women. The suspense mounts chapter by chapter, and Hannah awakens to changes far more than skindeep.

Hannah’s constant motion may mimic her author’s. After college, Jordan spent 15 years as an advertising copywriter. By her mid-thirties, she was a creative director in Austin, successful but stalled. “I was married unhappily, and I really don’t love Texas,” she says. “I always had this dream of being a real writer, of writing the Great American Novel. I became afraid I would wake up at 60 and regret that I never did it.” In short order, she got divorced, quit her job, and started writing short stories, submitting her best to graduate programs. When Columbia accepted her, she pulled up stakes and moved to New York. The whole metamorphosis happened within 18 months.

Once Jordan got moving, she didn’t stop. In the past decade, she’s relocated from upper Manhattan to a small house in Tivoli and back to Brooklyn; she’s also spent time at 11 writers’ colonies. “All the sort of time-sucking stuff of everyday life falls away,” she says of colony life. “You don’t have to shop, you don’t have to cook. They’re usually in an extremely beautiful place, and you’re in the company of other creative people. And there’s nowhere to hide from your work. At MacDowell, there’s no Internet in your studio and one bar of cell phone reception, so you better write.”

The more Jordan talks about writing, the more animated she becomes. Her dark eyes shine behind tortoiseshell glasses; at times, her whole body sways back and forth very slightly, as if she can barely contain her excitement. “People need stories, now more than ever, because reality is harsh for many people. I have often escaped into fiction. It’s a way of understanding other people, the human condition. It can create bonds with people whose experience is very different from yours. That’s what you’re doing when you write fiction—you are illustrating the lives of other people, for other people. So I do think fiction is important. I do think it can influence the world, by showing us our common humanity.”

Amen, sister. Jordan’s impassioned sermon recalls a passage in When She Woke. Hannah’s sister Becca marries a controlling man named Cole. When he joins a Klan-like vigilante group known as The Fist of Christ, Becca stops reading fiction because “Cole says it pollutes the mind with nonsense.” Hillary Jordan’s novels prove him deliciously wrong.

Hillary Jordan will read from When She Woke at Oblong Books & Music in Rhinebeck on October 8 at 7pm.