Many of us go through life wanting to know what’s behind the mask. But for University at Albany art professor Phyllis Galembo, the mask itself is enough.

Galembo’s latest work presents large-scale color prints of the masquerade, a centuries-old costumed ceremony she witnessed in the African nations of Benin, Burkina Faso, and Nigeria. Part documentary, part anthropology, part pure visual adventure, Galembo’s new images are the most recent incarnations of her decades-long inquiry into the masks, costumes, and ceremonial garb we humans use to conceal and reveal ourselves. The project has taken Galembo to Brazil, Jamaica, Nigeria, and Haiti, where she photographed Voudoo priests and priestesses in ritual dress—and even became one herself.

Now, her focus is on the revelers of the masquerade, who temporarily surrender their identities in favor of those of the spirit figures they represent. The work is on view in the exhibit “West African Masquerade” at Skidmore College’s Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery through December 30.

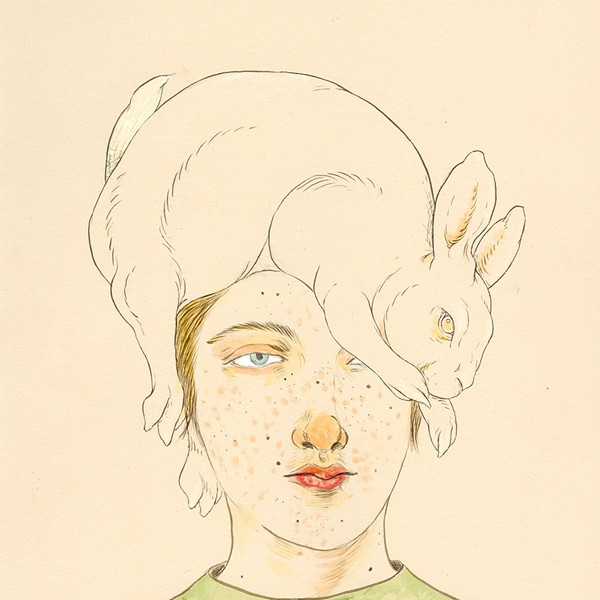

Galembo isolates the masqueraders, individually or in groups of two or three, against an improvised outdoor studio wall. She sets up her medium-format camera and single umbrella light and captures her image before the figures dance away. Their intricate costumes are made of crocheted yarn, wooden masks, and leaves. In some cases, the participants are barely recognizable as human. Only the least perceptible bits of skin allow us to remember that we’re looking at people rather than puppets or dolls. We confront these pictures in all their saturated tropical color as outsiders, privy to moments woven from a culture of strange religious rituals and an intimacy with nature that we don’t experience here.

Roberta Smith, reviewing Galembo in the New York Times, wrote that her images “are both portraits and documents, but their combination of dignity, conviction, and formal power gives them a votive aspect similar to European paintings of saints or kings.”

This latest work seems to have come unmoored from European perspectives. Galembo takes her viewers into exotic places inhabited not by people but by marvelous and mysterious spirits.

—David Brickman

Beginning the project

My interest in West Africa began in 1985, when I began to photograph priests, priestesses, and Nigerian altars, and soon after, I followed the root of the ancient African spiritual religion as it traveled to Brazil. My endeavors resulted in the publication of the book Divine Inspiration from Benin to Bahia, a series of photographs revealing spiritual diviners in their ritual dress. During the next several years, I continued following the African religion, working in Haiti, Jamaica, and Cuba, attending rituals and documenting the various orisa (deities). My interest in ritual dress expanded to collecting American Halloween and masquerade costumes, and I amassed over 500 American masquerades. The outcome of that project became the book Dressed for Thrills: 100 Years of Halloween Costumes and Masquerade, which was published in 2003.

Philosophy

My role as an artist has evolved to incorporate documentary traditions and images centered on cultures in transition. Photographing these various rituals and masquerades, I become enthralled in the experiences of other people. The idea of flux, something that could be here one day and cease to exist another, is important to my work. Traveling, the close interaction with different peoples, staying in villages and experiencing their unique cultures has made my life much more fulfilling. I am grateful that I have had wonderful opportunities to photograph various cultures, masquerades, and, foremost, people. Exhibiting my work at museums and creating books allows me to share the experience with a wide audience and celebrate our cultural differences and similarities.

Portraiture and process

Photographing the masquerade can be quite challenging, since the spirits are in motion and the streets are often frenzied and chaotic. To capture the richness of color, I prefer to use lighting equipment and seek out a proper background using sides of buildings and walls of homes to give the appearance of a tranquil portrait session. At times the masquerade will stop briefly for two shots and just run off. Other times, depending on the kind of masquerade, if it’s something I’ve commissioned, I may, through the talents of my assistant, convince the masquerade to stand in a neutral space where I’ve set up my battery pack and umbrella to diffuse the light. Permission is another aspect of the work, which often involves the whole village or village elders consenting.

On commonality

The magic of the masquerade inspires me. The people I have encountered appear to have enjoyed my curiosity and liked watching the act of photography. My fantastic assistants aid me in the process of encountering masquerades, translating and negotiating with village elders. At times I show them my other work and discuss my role as a teacher, so they know I’m serious about what I’m doing. Many of the people I encounter are artists, so we have some camaraderie. Culture is a treasured tradition and you have to respect that. My ongoing interest in portraits and ritual dress is the common thread in my work. When the mask appears, it is a new identity complete with its own language. It’s unusual to ask the masquerade to stand still for a few minutes to be photographed. In Nigeria, photography is extremely popular, as opposed to Burkina Faso, where my approach of having the mask stand still a few moments so I can photograph is something of an oddity. At times it is necessary to wait for hours for just one mask to appear.

The new work

In 2004, I returned to Nigeria to photograph masquerades in the area known as Cross River. A large portion of the images exhibited at the Tang Museum are from this period. During Christmas and New Year’s time around Calabar, Nigeria, masquerades made of natural materials such as leaves and branches captured my interest. During 2005, I photographed these Ekpo and Ekpe masquerades. This led me to Burkina Faso, where the tradition of costumes made of leaves is also found. During 2006, I traveled to Benin to capture the Gelede masquerades, which have their roots in Nigeria. From afar, it is quite easy to congeal the various masquerades, but on further inspection each masquerade has its own uniqueness, color, and reason. Masquerade appears at harvest festivals, funerals, coronations, and religious ceremonies. There are different ways that I approach encountering the masquerade, from commissioning a specific masquerade to appear to driving around for hours hoping to catch them during the Christmas season.