If artistic intellect could be described, like organic chickens, as free-range, Jared Handelsman would surely be one of its leading proponents. The day I came to speak with him, we sat in front of an open wood stove as he heated small rocks red hot, then imprinted them onto accordion-folded pieces of drawing paper. On a nearby table, row upon row of these ingenious little sculptures sat stretched out, punctured by the holes seared into them.

Handelsman’s intriguing photographic work is currently on view at the Center for Photography at Woodstock through March 30, and at Bard College at Simon’s Rock in Great Barrington through March 28. For more information, visit www.cpw.org or www.simons-rock.edu.

Rocks and space

I started using photography when I was doing installations outside, suspending a rock a few inches above where it had laid in the forest. I was fascinated with the fact that you couldn’t get inside the rock. You were picking the rock up, and you could see that interface with the ground that once was the identity of the rock. What kind of turned me off of doing them [the sculptures] was that to get opportunities to do them I had to resort to photography. I would show photographs in the gallery, and have a map of the grounds, of where to look for them, documentation. Often people would come back when I’d done three sculptures out in the woods and they would report that they’d found five of them. The photography was a way to disarm that—it identified the work, but it didn’t serve the sculptures well. I was amazed by photography, the latent image emerging—I love working in the darkroom, but it seemed like a shame that it was in the service of sculpture, and not serving sculpture very well.

At a certain point, I decided to just try some photographs. The first things I did were these photograms of rocks. As soon as I realized that I could get at the same thing, the same idea, using photography rather than documenting the sculptures, I stopped using it [photography] as part of the sculptures. They are photograms of quartzite pebbles, with very long exposures under an enlarger. Hour long exposures, and I chose rocks that have an irregular surface, so they sit up off the paper to allow light leakage around the edges. The white quartzite reflects the light off the white paper. I was just blown away that I could get into the same thing I was doing with the sculptures, in such a direct way. Seeing that space where there was that contact, and having an imprint of that mysterious place where gravity somehow becomes one thing, it becomes ground.

The tension of intentions

I like discovering things you would never have imagined, or could anticipate, without engaging in the process. I am really of the belief that it’s really valuable to engage in the process, but not because of the process, but because of getting somewhere you couldn’t imagine through the revelations of the material, that the material can actually show you things, if you’re open to it. I would often talk, years ago, about the tension of intentions. You kind of need an intention to engage in anything, but that intention is incidental, ultimately, because if you’re a slave to that intention, you risk missing the main thread that appears as a digression. It reveals something about that intention that’s profound, and also can open up a whole other way of thinking and looking at things. You need the intention, but it’s incidental, a catalyst. What I see often, with artists, is that people often get caught up in their intentions, and close down, learn not to get distracted from their intention, and really focus on perfecting something to the point where it becomes less and less interesting.

Event horizons

I studied philosophy [in college]. I was really into the philosophy of perception, and the relationship between what you believe and how you perceive. That, to this day, is the thing I’m most interested in art. I’m hopefully cultivating a way of seeing that is beyond what I can imagine or see. I’m not really the type of artist that does something in order to show what I see. I’m more interested in trying something and seeing what that might look like, and having that cultivate a way of seeing and thinking about phenomena.

In grad school I was just exploring all different media, trying different things. I was very process-oriented, and it had to do with phenomena. One sculpture I did that I really liked at the time—there was a big banquet for Guy Fawkes Day, a big fundraiser. I didn’t want to be a part of it, so I volunteered to clean up. The next day when I went in there, there were all these tablecloths made of big mylar squares. A lot of them were messed up, but a lot of them were pretty nice, and I saved as many as I could. I ended up doing an installation in my space, where I duct-taped them to the ceiling (it was pretty low) and made a spiral starting in the middle. It was an amazing sculpture. The easiest, simplest sculpture I’ve ever done, I think. People loved it—if you walked in it started shimmering, and it was very reflective. If you were on the outside watching while someone walked around to the center, the thing reverberated in response to them. So I was doing stuff that was ranging [between disciplines], and I felt very free about it.

Exhibitionism

At the [Albert Pinkham] Ryder show in DC, a dozen or so years ago, it was great because they showed you all the alchemy, the chemistry behind the paintings. It was also darkly lit, which I loved. That’s what I love about the [current] CPW show—because of the video, we had to dim down the lights in the space. Everything is so blaring these days. I love viewing work in minimal light. I think it taps into the imagination more. The artwork is an occasion for the imagination, blaring lights really kill that for me. I think it’s all about conspicuous consumption, these galleries just wasting a huge amount of electricity.

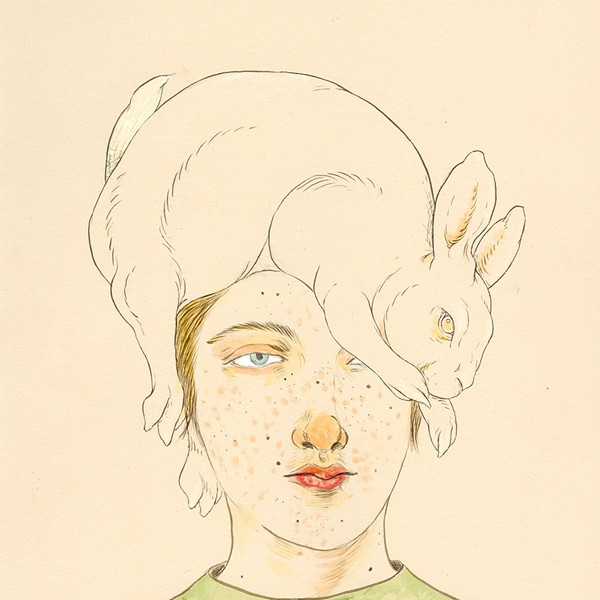

The space [at Bard College at Simon’s Rock] in Great Barrington is amazing, it’s got these huge skylights and big windows up high. I’ve got some family portraits there of my children, they’re photograms from a flashlight, and they were done on the floor. I brought a red light into the bedroom and put the photo paper down on the floor. They’re very much about the relationship of the body to the ground, the shadows. At the time I made them, when I was living in Provincetown, I showed them pinned on the wall. They read really nicely on the wall, but they have a much more psychological dimension on the floor. They become much more ethereal on the wall. When they’re on the floor, knowing that they’re about that shadow on the floor, they just read in a more grounded way.

And other modernist myths

I’m uncomfortable with this idea of novelty in art. I think of the work as being strange only to people who aren’t engaged in art. To people who are engaged in art, the photogram is the most rudimentary, basic thing—the earliest experiments in photography were photograms. When I first got into doing these things, a friend sent me a book from a show at the Met or somewhere, about Fox Talbot [who invented photography in the 19th century]. In it, there were these botanical exposures by moonlight. I think that’s so great—they were beautiful, little ferns. I had gotten down in the ferns, and was sort of chasing the moonlight at that time, and I was thinking that [what I was doing] was not innovative. It’s not about being novel, for me it was about stripping everything away to create a basic document of a phenomenon.