The Miller Middle School auditorium was packed, but quiet with anticipation as the 250 people sat scattered among the wobbly red velvet seats. There's been a national backlash against teachers, but at every sentence touting their heroism, there was a standing ovation. With each speaker, the life-size cardboard cutout of Governor Cuomo positioned near the podium was verbally hung in effigy. These were teachers, parents, activists, and community members who'd come together because their roles were being compromised, or children were anxious, or they feared corporate takeover, or they were concerned about the budget. But one thing was clear: They were all in this room because of standardized testing.

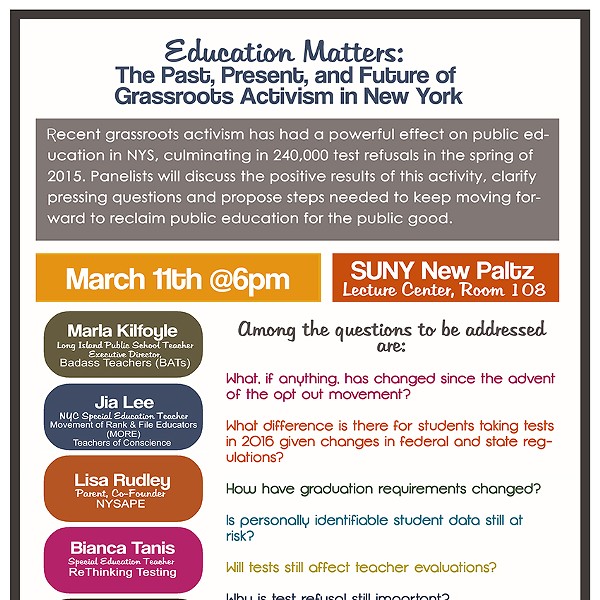

The test is the state assessments of Common Core English Language Arts (ELA) and math given in April to grades 3 to 8. The No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act mandates that states assess students through those grades, and Race to the Top mandates 95 percent participation so that schools can't pick and choose the students to artificially inflate their scores. But many people at the Ulster County Defends Public Education panel that night in February, co-sponsored by the parent-led NYS Allies for Public Education (NYSAPE) and local teachers' unions, are part of a growing movement that advocates families refuse the tests.

There have always been state tests, ever since we first tied public school funding to them in 1965. But with the gradual adoption of the Common Core standards—an initiative to establish consistency across states' ELA and math curricula and set the bar higher—testing has become a high-stakes game. Earlier this year, the governor came out with plans to increase the significance of test scores on a teacher's evaluation from 20 percent to 50 percent. While the speakers appreciated accountability, there was a fear that when it's so dictated by test scores, it could skew instruction. And they mentioned the various challenges within classrooms not taken into consideration by the tests. For example, while a student might advance to a third-grade reading level in the fifth grade, and it could reflect tremendous progress for him, he still wouldn't pass the fifth-grade test. "Each math lesson [in the Common Core] is so full of information, you could take a week to teach it," said panelist Kristina Flick, a Rondout Valley teacher on the verge of tears. She said it's two to three years ahead of previous math programs, so she needs to simultaneously teach basic skills. "I've been labeled effective, for now. But there will come a day when I may not be, regardless of my 22 years of devoted service."

When Bianca Tanis took the podium, the audience sat in rapt attention as she zoomed through the evidence. "On one front, our schools are being underfunded and starved of resources. On the other, our schools are deemed ineffective. Reforms have been put into place claiming to foster equity and access. But ironically, these reforms have resulted in test-driven education that deemphasizes social studies, art, music, and science, especially in high-needs schools. These reforms siphon funds from our schools, putting them into the hands of test makers. They weaken local control by democratically elected school boards."

For Tanis, it's personal. Her younger son is on the autism spectrum, and she knew the stress involved with being given a test he can't read, in a separate location, without help from the aides he trusts, would actually harm him. Only 2 percent of children with disabilities qualify for alternative assessments, and the criteria are stringent. When she notified Lenape Elementary in New Paltz that her son wouldn't take the test, there was some confusion. The school said that Tanis might have to keep him home for up to 12 days while tests were administered, since he couldn't cognitively refuse. Tanis called advocacy groups. It was through connecting with other parents that Tanis learned of her rights. And that grew into the formation of the statewide group NYSAPE, now a coalition of groups and a central hub for disseminating information and interacting with policymakers to bring in the parents' perspective.

Tanis believes the argument that those opting out are overprotective mothers who fear their children's failure is patronizing. Those at the panel deemed the testing products new and flawed, and testing itself not always the best assessment of student success, or the new catchphrase, "career and college readiness." They questioned the perception by education reformers, most of whom they claim have no experience in the classroom, as an accurate measure of a child's performance.