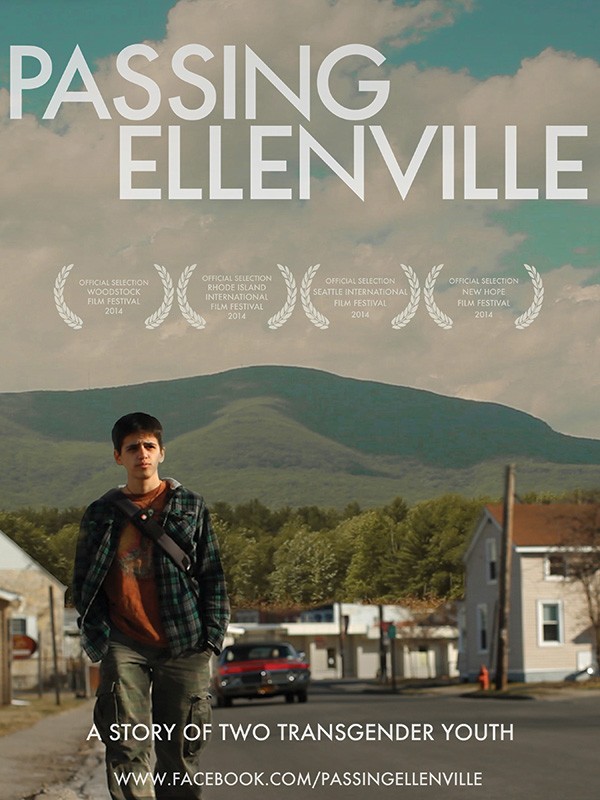

Interweaving the coming-out stories of two transgender young adults, the short documentary Passing Ellenville traces the evolution of James and Ashlee as they transition to correct their displayed gender. The film began for co-director and cinematographer Samuel Centore as his junior thesis for Pratt Institute, collaboratively built from the photography project of co-director and producer Gene Fischer.

At its New York premiere at the annual Woodstock Film Festival in October, Passing Ellenville was paired with Matt Livadary's feature Queens & Cowboys: A Straight Year on the Gay Rodeo. In pairing Passing Ellenville (rather than showing it with other shorts), the festival's executive director, Meira Blaustein, aimed to create a screening with an LGBTQ focus. It worked well for Fischer, whose filmmaking impulse stems from identification with the subjects' plight. "I see so much prejudice in the gay community against trans," Fischer says. "But we should be accepting because of what we've been through."

Unscripted, the film is, in some ways, a classic coming-of-age story with customary youthful angst and unrealized dreams. But it plunges deeper. "Rather than trying to take on broader themes in the transgender community," Centore explains, "we focused the film on how faith or profession interacts with being transgender." Ashlee's religious zeal conflicts with her affection for a drug-addicted convict, and James is essentially a runaway living in a group home. In the end, Passing Ellenville highlights the role that poverty plays in the subjects' sense of isolation.

Centore's breathtaking cinematography, with its selective focus and time-lapsed views of the Catskills and Route 209, intensifies the pastoral beauty of Ellenville, effectively amplifying the subjects' seclusion. "Ellenville is so beautiful and decrepit," Centore says. "It's very close to Woodstock, and it happens to have a micro community of transgender people. But they're stuck in the town, without communication with these other towns that would be more supportive of them." The regional advantages of beauty and community are inaccessible to James and Ashlee.

For James, participating in the film was liberating. "When there's no face or name to a situation, it's hard to get personal with it and understand," he says. "It's harder to make something taboo when it's out in the open."

The film lacks hope. There's just a glimmer of it as James walks away from the camera at the end of the movie, full of ambition. But it's this absence that works to engender the audience's empathy. Passing Ellenville sets out to understand the intangible need for acceptance and ultimately consigns the audience to see James and Ashlee for who they truly are.