When my parents left me in the custodianship of some hapless neighborhood teenagers to go out to dinner—in effect to get away from me, their first-born and at that point only child—I would eat a Swanson frozen meal for dinner (and imagine what might be in the doggie bag they'd bring home). I was a finicky eater back then. Foremost among a number of food-related peccadilloes was my insistence that no food item should touch any other food item on my plate. The potatoes should stay clear of the chicken and the salad shouldn't encroach on the dinner rolls. I found satisfaction and comfort in maintaining order with my food and keeping the messy indeterminacy of everyday life off my plate. (I did not use the phrase "messy indeterminacy" when my mother placed the peas alarmingly close to the rice. Instead, I would angrily sob "No no no no no no no," thus conveying my despair over a disordered universe.)

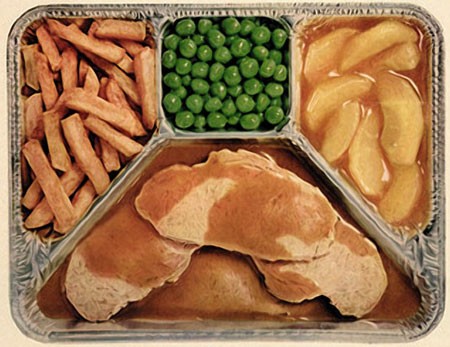

Swanson frozen meals were my jam. They were compartmentalized. The aluminum tray that they came in could go straight from the oven to the dinner table (or TV dinner tray if I could lie convincingly to the babysitter). Like pockets of nutritional purity, all the components of the meal had their own place: the Salisbury steak, the mixed vegetables in seasoned sauce, the whipped potatoes, and the apple cake cobbler. The Swanson dinner tray represented to me a next-generation piece of technology that left mere plates behind. Why settle for a level ceramic surface that allowed for the accidental mixing of food when a contraption existed to keep them apart? And despite my earnest entreaties, I was not allowed to wash the Swanson frozen dinner tray and use it as my normal plate. My parents were cruel.

My fastidiousness around food waned in college, right around the same time my interest in other regimented activities, like daily hygiene practices, lessened as well. It seemed a natural evolution. In the lecture hall, my head was filled with theories deconstructing my prior assumptions about the ordered universe. (You mean to tell me that people writing history books have a viewpoint and an agenda that's used to reinforce the dominant paradigm? What's next, you gonna suggest the government lies to us too?) In the dining hall, I began to understand the pleasures of mixing food types, and that a forkful of mashed potatoes and meatloaf could be tasty. (This is surely the tamest anecdote of college experimentation ever written.) Once the barriers of my traditional categories (objective certainty/subjective uncertainty, meatloaf/mashed potatoes) started to break down, my perception of reality got a whole lot more complex and interesting.

My transition from a fussypants child to a slightly less rigid adult occurred to me this month as we were putting together the June issue. There seems to be a thematic undercurrent of categorical confusion this month. Which got me thinking: Aren't some of the best things created by mixing categories? Mixed-breed dogs, for example. Or what about "Hamilton," the Broadway blockbuster that sets the story of the First Secretary of the Treasury to hip hop? (Local boast: "Hamilton" got its start at Powerhouse Theater in 2013. What future Tony-winner will be debuted at Powerhouse this year? Find out in our Summer Arts Preview, page 55.)

The porousness of categorical borders came up in Peter Aaron's conversation with indie rocker Will Oldham, aka Bonnie "Prince" Billy ("Son of the South," page 99). Oldham, known as a lo-fi savant, also loves the extravagant MGM musicals of the `40s and `50s. And he sees no distinction between the two. "What drew me to the MGM movies as a kid was the idea that you could wake up, look around, and just sing about anything," Oldham says. "[Both styles] are about blurring the lines between music and life." It's interesting how traditional categories break down under the slightest scrutiny.

Taking that line of thinking further, I would suggest that the Hudson Valley is a place that thrives on eclectic combinations—in its people, its institutions, and its art. The line between art and life is completely erased in the home of Kat O'Sullivan and Mason Brown ("Stitched Together," page 40). Decorated in a riot of colors and conceived in fanciful flair—there's a smiling set of teeth painted above the front door—the house reflects the couple's continual artistic output and willingness to defy convention. It's a strange coincidence that one of the first places that O'Sullivan visited in the Hudson Valley before moving here was the Egg's Nest in High Falls, whose bric-a-brac aesthetic mirrors her own.

Margot Becker, organizer of Trash Fest ("Trash as Treasure," page 97), is blurring the line between trash and art. (Insert your own wisecrack about how so much art is trash to begin with here.) For the month of June, the Marbletown Waste Transfer Station will be the site of an art show, the artwork assembled from materials salvaged at the dump. There'll also be a concert featuring instruments made of refuse. This is Trash Fest's first year, and time will tell whether the line between art and trash needed to be blurred, but its mere existence celebrates the best of the genre-eliminating spirit of the region.

One organization that's been breaking down perceived barriers for many years is the Triform Camphill Community farm village in Columbia County. Since the 1980s, the farm has been a place where young adults with developmental disabilities work and live side by side with resident families and volunteers. At Triform, the emphasis is on inclusion and creating a place for the entire community to balance work, life, and creativity. Wendy Kagan's report on this incredible intentional community ("It Takes a (Farm) Village," page 88), is one of the most uplifting and inspiring pieces we've published in some time.

But sometimes, just like the eight-year-old brat I was, you seek purity through limitation. Enter brewer, author, and fermentation enthusiast Derek Dellinger. Ever wonder what the Icelandic national dish, hakarl, tastes like? Well, Dellinger will tell that it tastes like what it is, rotten shark. He ate it because hakarl is fermented. And Dellinger spent a year eating only fermented foods, taking detours through some bizarre culinary alleyways ("The Fermented Man," page 80). Ever notice how the word "fermented" rhymes with the "demented?" If I could only think of a fitting rhyme for "Swanson."